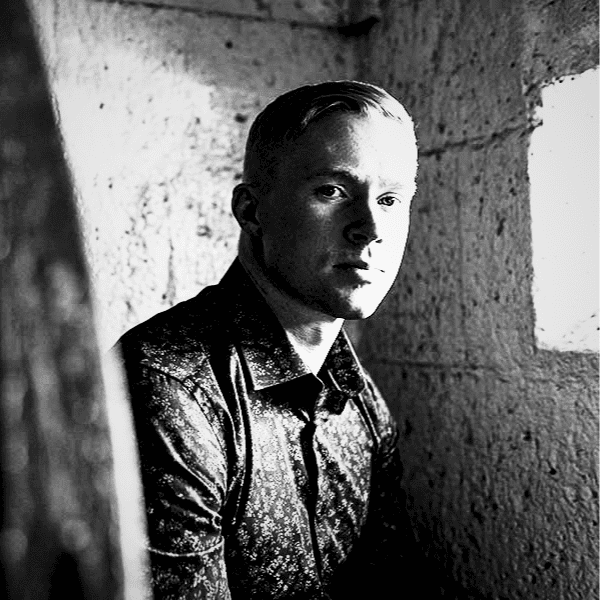

Luke Anderson On Transformational Employment Pathways For Formerly Incarcerated Australians

Luke Anderson’s personal journey through the corrections systems to advocacy is one of resilience, transformation, and hope. His lived experience has shaped a deep commitment to justice reform and second chances.

That journey led him to create Fair Threads, a social enterprise that provides prison-compliant clothing for inmates in Victorian correctional facilities. Every purchase supports their mission to create job opportunities for ex-inmates, helping to build stronger, safer communities.

Each item is carefully selected and packaged for secure delivery to correctional facilities, ensuring ease, compliance, and dignity for inmates. Luke is focused on building Fair Threads into a sustainable and scalable business that supports long-term reintegration.

Luke discusses the challenges for formerly incarcerated individuals to access employment and reintegrate into society, and creating purpose-led social enterprises fostering the forward-focused mindsets critical for long-term success.

Highlights from the interview (listen to the podcast for full details)

[Indio Myles] - To start off, can you please share a bit about your background and what led you to work in social entrepreneurship?

[Luke Anderson] - I am first-generation born in Australia. My family’s roots are in Norway and England. I grew up in a poor household as a Smith Family child in a housing commission. I had all the typical risk factors for a young man who might end up in trouble. I think I developed an entrepreneurial mindset early on because of the conditions I grew up in.

Over time, things escalated, and I eventually found myself so short on resources I felt I needed to take matters into my own hands. Unfortunately, for me, that meant stepping into organised crime, which ultimately led to my incarceration. While prison is never a good experience, I had as positive of an experience as one can in that environment. It gave me the opportunity to reset and reflect on who I am, why I am the way I am, and why my family is the way they are.

One major realisation was I liked business and wanted to do something more than just work a job. Eventually, I came up with the idea for Fair Threads, and over the past seven years since my release, I’ve discovered what I had envisioned is in fact a social enterprise. There’s been a huge amount of learning I’ve done along the way which ultimately brought me to where I am today.

You’re the founder of Fair Threads. Can you explain a bit more about this social enterprise and how it supports the rehabilitation and reintegration of former inmates into society? I’d also love to hear how your personal journey within the justice system shaped your approach to impact?

Fair Threads at its core is an online store where friends and family of inmates can purchase approved items to be sent into their loved ones in prison. At the moment, the items you’re allowed to drop in includes things like shirts, shorts, socks, jocks, singlets, pyjamas. There’s a very particular set of rules and compliance requirements around these items. For instance, shirts can’t have a V-neck, visible branding, top pockets, or drawstrings.

What often happens is people will go to stores like Target, Kmart, or Cotton On to try and find clothing they believe meets these requirements. But when they arrive at the prison (usually during an already emotionally charged visit might I add) they’ll be told by an officer who is simply doing their job that an item doesn’t meet one of the rules.

This can be incredibly frustrating, especially when people have spent time and money they often can’t spare to source these garments. It can lead to uncomfortable situations at the gate and can even have flow-on effects into the yard for the inmates involved.

By providing a central, compliant source for these items, we’re making things easier for families and staff, while also reducing the potential for people to attempt to smuggle things in. It ticks a lot of boxes. There’s social impact, operational efficiency, and innovation involved in this process.

The greatest impact will come from the fact Fair Threads will employ and create transitional employment pathways for people exiting the justice system. Hopefully, this will demonstrate what’s possible when you leverage the supply chain to create fantastic outcomes, particularly within the justice sector.

As for how I came up with the idea, like I mentioned earlier, I went to prison myself.

I served a sentence of four and a half years. Three of those years I was in custody, and the remaining year and a half I was on parole. I was in the somewhat unique position of having a partner who supported me throughout the entirety of my prison journey.

I met her six months before I was locked up and, in hindsight, it’s worked out. But at the time, I think most people thought she was foolish, or that something was wrong with her, for deciding to stick with a bloke like me.

The person I am today is far removed from who I once was. Her commitment to stand by me was the first opportunity I had to create healthy goals in my life. I looked at who she was and what she was doing, and thought, “Far out, what have I got to offer?” I was just a kid who had grown up poor, fallen into crime, and ended up in prison. What could I possibly give her to make her want to stay with me?

I made a critical decision: I would use my time in prison to become the she deserves. I looked five years into the future and asked myself, “Who will I be then to give a woman like that what she deserves?” That goal motivated me to engage in psychology appointments, counselling, and drug and alcohol programs. I took on employment within the prison, and later, when I moved to a minimum-security facility, I was able to work in the community, volunteering with the Salvation Army.

All the while, I kept thinking that when I got out, I wanted to run a legitimate business. I didn’t yet know what it would be, but I knew I needed to think carefully about it. One day, my partner was dropping off items for me and she had the frustrating experience of having them knocked back. It was just a few t-shirts, the same type she had successfully dropped off before. This time, a staff member interpreted the rules differently, and the items were refused. She was annoyed, and it was actually her who said, “Why isn’t there just a store where you can buy this stuff?”

I thought, “That’s a good idea, I’ll write it down and flesh it out.” While I was in prison, a lot of people laughed at me, but I asked the education officer to print me a survey sheet in Excel. I went around from unit to unit asking people how much property they had dropped in, how much their families typically spent, and how often they received these items. From that, I started building some basic sales forecasts.

None of it was even close to accurate compared to the data I have access to now, but it gave me a starting point. Developing the idea became a fantastic mental outlet for me; a North Star to focus on for the future.

I had a few other business ideas as well, but Fair Threads, with its purpose-driven element, was always the one I wanted to pursue. It’s coming up on 10 years since I came up with the concept—because I developed it while I was still inside. Now, I’ve secured seed funding, and we’re ready to start kicking things off.

What key principles are most crucial when working with formerly incarcerated individuals to help them reintegrate into society, and how do you embed these principles within Fair Threads?

This question takes me back to my release. As I’ve said, prison is a horrible environment. You’re deprived of so much and feel like life is slipping you by. There’s limited genuine contact or intimacy with people. When I say intimacy, most people think of it in a sexual context, but if you look up the meaning of intimacy, it’s really about having a deep understanding and connection with someone. In prison, that’s incredibly rare because you’re constantly in a survival mentality. It’s taxing, and you’re surrounded by people caught in the revolving door of reoffending.

One thing I’m proud of is that I navigated the need to survive while still engaging in the programs and services I needed. I remember looking around at others and thinking, I’m ready to get out, I’m prepared, I’m going to hit the ground running. The truth is, no one can be fully prepared. You don’t know what’s around the corner or what you’ll really need until years later, when you can look back and think, Oh, that’s what I actually needed at the time.

While you’re inside, there’s often a strong “blue versus green” mindset: us versus them. I was part of that. You get fed constant warnings that make you anxious about being released. Because my offences were drug-related, I was told by people that every time I got pulled over, the police would strip my car, do the same to my wife’s car, or that I’d be sent straight back to prison just for accidentally running into an old associate. It puts you on edge.

I’m not someone who usually suffers from anxiety, but I felt it often after release. Then, when you start seeking employment, you face constant knockbacks. People finding out you’ve been to prison will say, “sounds good, but unfortunately we can’t give you the job.”

I kept getting the same response: Really proud of you mate, but unfortunately we can’t give you the job. It wasn’t until I started being completely upfront from the beginning and explaining where I’d been, where I was now, and where I wanted to go that I had success. That approach landed me my first full-time job.

The reason I share this is because, when it comes to helping people transition back into society, whether through employment or other services, it’s important to recognise the external forces at play. Today, there’s a strong narrative telling people coming out of prison that they are victims and that the system is against them. In many ways, it’s true that most people in prison have experienced significant damage in their lives. But while those statements may be accurate, they can also be unhelpful if they trap someone in a mindset where everything is stacked against them.

The reality is that you went to prison for a reason. You did something wrong, and the only person who can truly change your circumstances is you.

In Australia, there are many services available for people exiting the justice system. The effectiveness of these services varies, and personal circumstances differ greatly. For some people, unfortunately, achieving a good outcome may be unlikely.

When building Fair Threads, this thinking is central to the culture we’re creating and the example we want to set for other organisations. We need to understand the difficulties people face when leaving prison, but we must not foster a mindset that keeps them stuck where they are. Instead, we aim to nurture a forward-looking mindset, helping people to take productive steps now to build the life they want to be living in five years’ time, rather than languishing in their current situation.

You’re focused on building a more inclusive workplace for people exiting the correctional system to help them reintegrate into society. What have you learned from creating these inclusive workplaces, especially for a community with such complex needs?

What I’ve learned is that this space is the Wild West at the moment. There are a lot of great ideas out there, but the truth is, nobody actually knows for certain what works yet.

From my own experience (and from keeping in touch with a lot of blokes I knew inside), I’ve seen some people go straight into a regular job, find their feet, and remain out of prison five to ten years later with no signs of heading back. Then there are some business models where 100% of the workforce has been involved with the justice system in some way.

I’m not convinced either approach is ideal. If your entire workforce has been through the justice system, work can end up feeling like an extension of prison. While there are clear positives to having an empathetic and understanding environment, there are also cultural risks and limitations to your skill pool when hiring from only one cohort. When you come out of prison, it’s incredibly valuable to have regular contact with people who haven’t shared those experiences.

Out in the real world, not everyone will understand your challenges, nor do they need to. What’s important is accepting that you need to build your own support network, find the right people, connect with your culture (whatever that may be) and establish healthy habits. The people you meet at work can absolutely become great friends, but your work should support your life outside of work. You don’t want the two to completely merge, and you need to be mindful of that.

I’m not claiming I have the definitive answer. But from my observations and working with corrections on lived experience panels, producing a 16-episode series on positive transitional employment stories for the department, and collaborating with employment agencies and businesses in this space, I see a hybrid work environment as the best approach for now.

As an AMP Foundation Tomorrow Maker, you’re currently getting support to develop and grow Fair Threads. What have been your reflections and learnings from the support to date?

It’s been interesting. The AMP Foundation has two streams for support, Spark and Ignite. I applied for Ignite last year feeling confident I was ready for it. I got through to the interview stage, and they told me they liked what I was doing, but they thought it would be better for me to do Spark first and then move into Ignite. I’ll admit, I was pretty annoyed about this. I thought that if I did Ignite straight away, things would kick off and away I would go.

I’m very happy to admit I was wrong. The Spark program last year was exactly what I needed. I’ve been working on Fair Threads for close to a decade, but most of that time was focused on understanding people within prison and what I was going to sell. The social enterprise elements of being able to clearly articulate my purpose and measure impact was something I needed to develop further.

Getting out of prison is one of the most isolating experiences you can have. Starting a business is also one of the most isolating experiences you can have. Then you add another layer of complexity by saying you’re running a social enterprise, which is still niche within business.

It can feel like you’re operating in a very small world. It’s becoming more well-known, but five years ago, in a room full of business people, saying I was running a social enterprise often got the reaction, “that sounds like a not-for-profit, get away from me!”

Through Spark, and now Ignite, I’ve been able to meet like-minded people. The structural knowledge and insights I’ve gained have been fantastic and eye-opening, giving me much more confidence to hold my own in conversations. But the biggest benefit has been the network. Loneliness is a killer, and feeling like there are people in your corner on a journey like this makes a huge difference, especially if you’re genuine about your mission.

We often say we’re doing good work and important work, but it shouldn’t come at the expense of your health. Having this kind of supportive network has been critical for me as I navigate the different stages of Fair Threads and my own growth as a social entrepreneur.

Do you have any advice for people who are trying to create their own social enterprise or impact-led organisation to change lives?

Go to as many networking events as you reasonably can. That’s helped me enormously. I’m based in Geelong, and I’ve been attending SENVIC events for years. Just learning and talking to other people in the room, before throwing yourself headlong into whatever it is you’re planning, can give you a much better understanding of the landscape.

It’s important to acknowledge that while there are a lot of people doing great work, there are also people who see the opportunity in labelling their business as a social enterprise without truly committing to the model. You don’t want to align yourself with those types of people, and often, they’re not particularly innovative. Yes, there’s a social element to what they do, but it’s similar to greenwashing, a standard product with a bit of social impact “whacked over the top.” You have to be careful not to unintentionally create a business like that yourself.

If your cause is important and you’re passionate about it, that’s great. But will your business actually work? Is it solving a real problem for someone, beyond addressing a perceived social or environmental issue that your customers might not have any direct connection to?

Innovation is key to building a social enterprise that will truly stand up in the market. Simply putting a label on something isn’t enough to tug on people’s heartstrings. You need to solve a real problem.

What inspiring projects or initiatives have you come across recently creating a positive change?

I’d like to give a shout-out to my fellow Tomorrow Makers, Reboot Australia. As I’ve said before, it’s the Wild West right now in the transitional employment space. Where we are today will look very different to where we’ll be in five years’ time.

I really like the way Reboot Australia goes about its work and how they represent the men and women they’re placing into jobs after prison. I’m eager to collaborate with them in the future. I think people should definitely look them up and follow their journey.

If you’re a large business looking to address skills or labour shortages, I recommend having a conversation with them. What they’re doing is absolutely fantastic.

To finish off, what books or resources would you recommend to our audience?

There’s just one book I’m going to recommend. Many people may have already read it, but it was absolutely pivotal in helping me foster a positive mindset while I was still in prison. The book is Man’s Search for Meaning by Dr. Viktor Frankl, a Holocaust survivor who was imprisoned in Auschwitz during World War II.

In the book, he speaks about how, even in that horrific environment where his body was completely restricted, his mind remained free. Even when life feels entirely hopeless, there are still tiny actions you can take to influence your environment, even in minute ways, that can ultimately determine whether you survive or perish.

When you apply that mindset to other areas of life, those small, deliberate actions can be the difference between success and failure. I strongly recommend this book.