CV Harquail On Feminist Businesses Challenging The Status Quo

CV Harquail, PhD, is an author, management scholar, consultant, tool maker, and rabble-rouser. She is a co-founder of FeministsAtWork.com, a co-producer of the Entrepreneurial Feminist Forums, and a facilitator-catalyst in the Feminist Enterprise Commons.

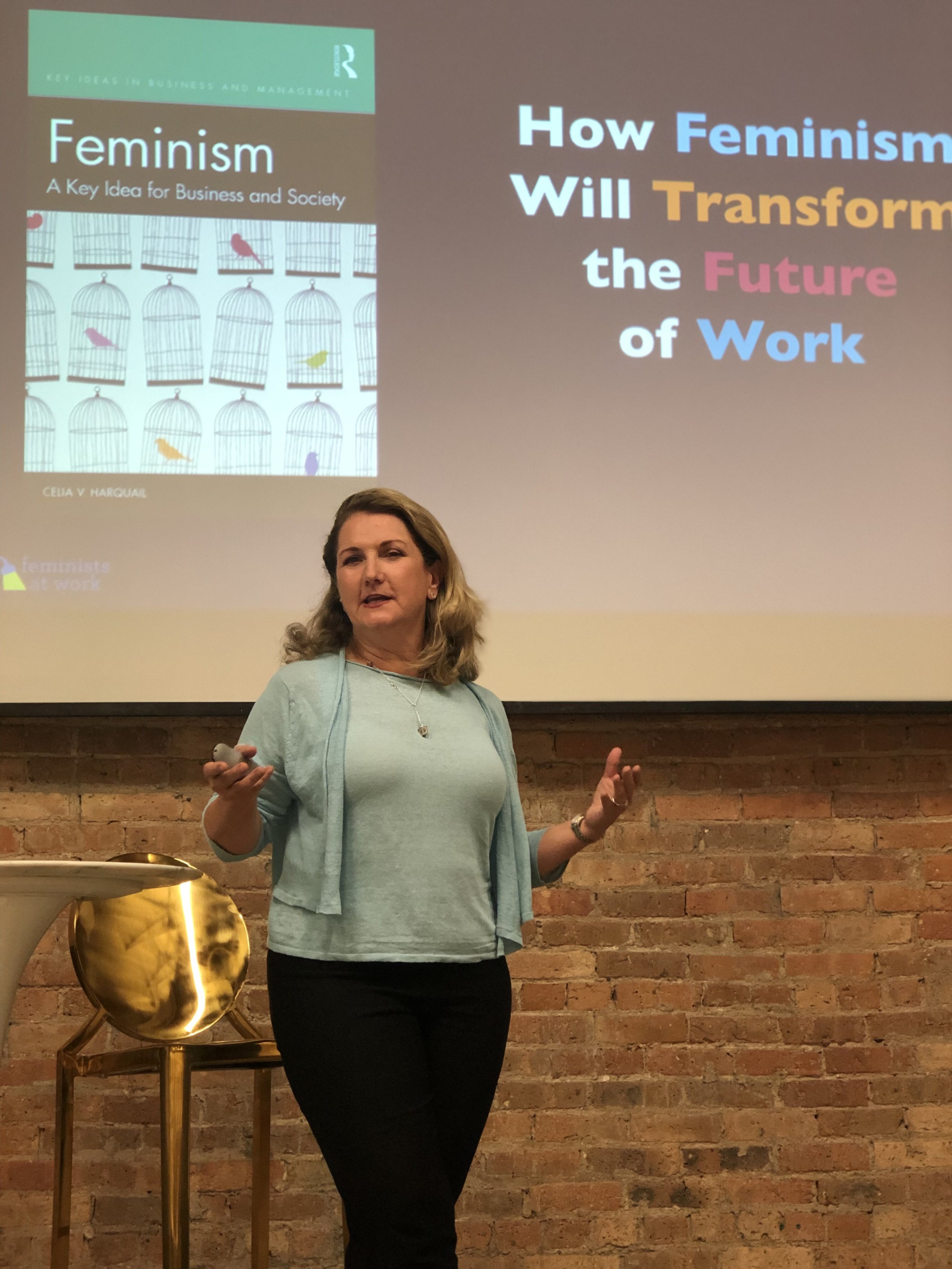

CV is the author of Feminism: A Key Idea in Business and Society (Routlege, 2020) the first book to explore business practice through a feminist lens. To help entrepreneurs build feminist principles and values into their enterprises, products, and leadership, CV designed the Feminist Business Model Canvas (2015). CV teaches workshops on all facets of feminist business and feminist business praxis.

An award-winning teacher and researcher, she taught entrepreneurship and organizational change at Stevens Institute of Technology and The Darden Graduate School of Business at University of Virginia. She received her PhD in Leadership and Organizations from the Ross School of Business, University of Michigan.

CV lives in the traditional homelands and waterways of the Council of the Three Fires: the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi Nations, also known as Chicago.

CV discusses how, why, and what it looks like to explore business through a feminist lens, and the frameworks allowing changemakers to effectively challenge the status quo.

Highlights from the interview (listen to the podcast for full details)

[Sarah Ripper] - To start off, could you please share a bit about your background and what led you to where you are now?

[CV Harquail] - I wish I knew what led me, but I do know what has propelled me. What has propelled me is my whole life I have been a feminist and I've been concerned about social justice and trying to change the world to make it a better place. Even as a kid, I was that insufferable nine-year-old insisting that everyone celebrate Earth Day. I was the 13-year-old who in my junior high yearbook, underneath my name, it says, "believes in women's lib," which is what we called it the late 1970s. But I've always been a feminist. I've always been aware of oppression and in tune with this idea that we want to make the world a place where all people can flourish equally. The business part is also weird because I was again a weird kid who was always interested in business. I was fascinated by how people got together to make stuff, and how you could make stuff more effectively and how you could get more people interested in the stuff that you made. Both of my parents were in business, my mum in marketing, and my dad had a retail store, and so I grew up around business and thinking about it. It took me a while to make the connection between the two, and in my lifetime, I've gone in and out of making that connection sometimes more effectively than other times.

In college I realised that a feminist political theory or a feminist lens was a way to understand questions like leadership, collaboration, power and agency.

When I was first working, I was working in a soap manufacturing plant doing organisation development and trying to figure out how to get teams more involved in taking charge of the manufacturing process and trying to do that work, which was really very early organisational change work. I just got this sense that people who were doing it, there was something missing underneath it all, and I didn't realise that what was missing was no one was acknowledging how at odds the goals of business were from the goals of a high commitment, worker driven, shared leadership work system. I didn't realise that those two things were in such opposition that it was almost ridiculous to imagine that we could create one in a plant that sold ivory soap. When I went off to graduate school, I was sure I was going to get my PhD in Feminist business and that I would become a feminist business expert and teach people how to change the world through their businesses. What surprised me was how I was told that was not an appropriate thing for anyone or someone like me to be doing, particularly not in the early nineties when shareholder value was such a big issue and money, profit and getting promoted were all the things you're supposed to talk about or teach about to MBAs. This is a long answer, but I've always had this hybrid thing going on where in the business school getting my PhD, I was the weirdo who taught in women's studies, and when I was teaching in women's studies, I was the person they couldn't trust because I hung out with the capitalists. But to me there was always something that each of them had for the other, and I wanted to figure that out.

I got distracted, I went off and joined a fancy schmancy business school and taught MBAs and executives how to be leaders. Then I moved and started teaching MBA students how to develop small businesses and use lean start-up methods to figure out the businesses that they wanted to build. It wasn't until maybe 12 or 13 years ago that consciously those pieces came back together. Part of it was connecting with my partner in rebellion Lex Schroeder, who is also a feminist, and together we created this Think and Do tank called Feminist at Work. What we tried to do was bring together mostly women who were interested in being more feminist in the workplaces that they existed in. We had a whole bunch of different practices that they could use to raise women's issues and raise issues of Anti-oppression, racism, or issues about the environment, whatever they needed to do to raise questions, and we wanted to support them in doing that. Lex and I were doing this work, and in the meantime, I'm teaching all of these student teams how to develop their business ideas using lean start-up tools, and one day Lex said to me, "why don't you ever combine those things and teach people how to do feminist businesses with these lean start-up tools?" I said, "interesting idea, except that all of those tools are designed to build businesses that satisfy the criteria of the status quo to satisfy the criteria of investors, to satisfy the criteria of marketers, to satisfy the criteria of owners and not to promote any of the values that I knew a feminist organisation could promote." That invitation from Lex to start putting those things together got me thinking about making some tools, and one of the things I love that we don't talk about enough is this idea that all the tools that we have reflect a worldview. They reflect a set of priorities, and they reflect a set of objectives.

If you use conventional tools uncritically, you're going to build a conventional business. If you use a tool that teaches you how to extract as much as possible from your supply chain or your workers, or to be as politely authoritarian as possible, if you use those tools, you're never going create a business that's going change the world.

You must change the tools so that you can help people change their business practice. I started by making a tool for all those feminists working in organisations, that was basically to help them build consensus around a change project. It was a canvas like the business model canvas, and I was doing workshops on this, and I got a call from this person in Toronto who said, "I want to see more of your feminist lean business canvas." I said, "I don't have one." She said, "what about that thing that you've been doing, it's a business model canvas." I told her it's a project canvas, but she wanted to know where the business model is canvas? Within a week I'd started building the feminist business model canvas, and that person, Petra Kasumuch, is now my other partner or another partner in rebellion (another person promoting the feminist business and feminist entrepreneurship conversation). But it was that thing where friends of mine basically invited me to bring together interests that I had kept separate because I couldn't figure out how to integrate them. That's basically how I got into doing Feminists at Work and the Feminist Enterprise Commons; it was with both of these women trying to build a network in a community of folks who want to use feminist principles, feminist wisdom and feminist practice to change how we do business, whether that's how we develop products, how we actually market things or how we treat our financials and our cost accounting.

In the work that you've done, what are some of the impacts you are seeing happen? What are some of the ripple effects?

I had been writing a blog for a long time called Authentic Organizations, and I'd been writing about what I called Progressive Organisational Movements, so those things like sociocracy or horizontalness or Sustainability or regenerative business. I just had this very not searchable, not keyword friendly name for it of Progressive Organisational Movements. The more I wrote about it, the more I was writing about feminism, but not using the term feminism, and working with Lex, I started to use that language more clearly and with more conviction.

As I did, people found me. That's how Petra found me, she was Googling one day for feminist and entrepreneurship, and that's how she found me. What happened was she found me, I found Kelly Deals, who's my third partner in rebellion, she's a feminist marketing strategist, and together we started connecting our conversations and highlighting each other's work and circulating stuff around and reaching out to people till we got enough interest that Lex, Petra and I decided to host a conference, and so we had a little conference in Toronto in 2016, that was the first time we used the Feminist Business Model Canvas and brought people together. That was where I met Vicki Saunders (she came to the very first one of those conferences), and then we did two more conferences larger and larger after that. Our third one had 250 or 300 people come to the two-day conference.

What we did was put the words feminism and business together and put the words feminism and entrepreneurship and feminist and start-up out into the ether and we started to find people who were interested.

We built a network that way, and a lot of that work was simply just stating the truth that a feminist approach to it would be like this. Some of it was around offering clarification, because one of the things I realised early on was that some people would be really attracted by the term feminist business, even though they didn't know what that would be, but they were positive and then other people would be sceptical.

How could there possibly be a feminist business? Is that a business run by chicks with hairy legs wearing Birkenstocks who are vegans? What is that? This is one of the things that I discovered when I was working on my book was that the biggest obstacle to people adopting and understanding and getting excited about feminist business practices was that they just didn't know what feminism was, and that's on purpose. Not my purpose, but I think the world has conspired, the status quo has conspired, convention has conspired to make feminism an opaque kind of word, and to make people want to keep it at arm's length. Even folks who were excited about it were tentative.

One of the very first things I had to do at the very first entrepreneurial feminist forum was I had to give a keynote on feminism 101, and I had to say things like, "we're defining women as a political category and anyone who wants to be part of this category is included in this group," And that was a mindblower for some people. I offered my own definition of feminism, which also freaked people out because they'd never heard it described this way before. Probably the most common definition of feminism that you'll get if you ask someone who's taken women's studies, she or he will refer to Bell Hooks who said that feminism is a movement to end sexism and sexist oppression, and then they'll stop there. But what I've concluded in my own research and my own thinking and writing about feminism is that feminism is a lot more that we feminists should claim.

Feminism is a movement to end sexism, misogyny, patriarchy, and all oppressions. Once we understand that all oppressions are linked, a feminist movement must address all oppressions.

Sure, it can use gender or sex, misogyny, patriarchy as the leading lever, but all of this stuff is connected, and we know that. We also know that feminism isn't just something that people with vaginas do, it's something that anybody can do because it's a perspective, it's a political orientation. It's a set of values that has nothing to do with whether you're male or female or something else. It's a statement that you make; it's a belief system that you adopt and advocate. That whole ending oppression isn't even half of it because that's all about what we are opposing. We're opposing oppression, but what are we proposing? What's the constructive part? That is two things. The first is that goal to establish equality, political, social, economic equality, which isn't sameness because that's a way that an anti-feminist move has been to diminish this concept of equality, and so people think of it as equal treatment under the law. That's not equality, equality is you are a human who is valuable, they are a human who is valuable, I am a human who is valuable and together we are all equally valuable, equally responsible, equally accountable with equal opportunities to make a difference in this world. That's the feminist view of equality. But it doesn't stop there either because it's not about getting rid of oppression and saying, "hey, here's equality!" It's about doing something with that equality, so the third element is working to create a world where all living things flourish. Not just women flourish, and not just women and men and humans flourish, but all living things.

The more you understand the feminist perspective on not only what's missing from how we work in the world, but also what's most desirable, it's flourishing and that notion of flourishing as the focus of feminism is very deep in feminist philosophy.

You must have studied it to know that it's there. Part of my role has been pulling these things altogether and putting them into a definition that people can recognise. I have a colleague who has created this tool called The Flourishing Business Canvas, it's a whole organisation design canvas. One day, a couple of years ago, he emailed me and asked, " can you tell me where this idea of flourishing came from?" I like, said, "Oh Anthony, you do not want to have asked this! Let me send you 20 PDFs of all this really obscure feminist philosophy, it's in there." It's in there because that's the thing that you understand when you are sentient and constructively critical about that experience of not being in the centre, that experience of not being in charge, not having agency and what would I do with this agency? Would I take charge? But once I did, once we did, what would we do with this agency? What is this ultimate role for it, and that is flourishing for all living things because they're all connected. I know that's speechifying there, but it's something important to know. That's what feminism is, and it's not man hating and it's not Cheryl Sandberg getting to be the COO of a company that steals your life data from you. That's not feminism.

What are some of the key challenges and opportunities as a feminist leader that you see in the social impact business space?

The very first thing is to let people know that all the things they are trying to do have been tried by feminists in business, by activist entrepreneurs in the past. They've not only been tried, so there's not only the history of that experience and the story of what's worked and what hasn't, but there's theory behind it. There's theory about why it should have been done. There's theory about how distant what we desire is from what we're able to do and how to make that okay. There's thinking and wisdom around these practices that if other social entrepreneurs would glom onto it, might make their work easier and they might feel less alone, and they might have different places to turn for reading. But the part that worries me the most, and it has worried me about social entrepreneurship since the day whoever it was coined the term (relatively recently I would say), that is that

many social enterprises are inadvertently and unconsciously reinforcing the status quo, reinscribing negative practices, finding other ways to exploit more nicely, to extract more gently.

They are modifying and sometimes not modifying at all; they're trying to augment over on the side we'll suck this value out, but we'll give you some extra over there for a buy one, get one free. There's a little bit of that; there's a lot of incremental adjustment that's ultimately not that effective, and then they miss the opportunity to use all these tools of business differently to use them as what we call assets for change. Your bookkeeping system is an asset for changing business. Your hiring process is an asset that you can use, you can deploy differently, you can reimagine to practice things differently.

We know that every time we practice something differently, it may not be perfect, but it takes us the next step so we can see the next step or two. A lot of times people will ask me what does a feminist economy look like and what's a perfectly feminist business?

I'll say, I don't know, and they'll get all irked at me because I'm supposedly the expert. I don't know, because it's something we will create together. It's a co-creation process, which I know is something that a whole lot of social entrepreneurs like; they get that part that we are trying to co-create a new reality. We're trying to do system change in a new reality. There's that question of how deliberately are we using the tools at hand and the practices at hand? Are you using your daily stand-up meeting to challenge oppressive power relations or to practice care for each other? A feminist business practice would be to ask that question.

How do you take those concepts and assets you have just outlined and apply them?

The most important thing a feminist perspective brings to social entrepreneurs is to tell social entrepreneurs that they're not going to make a difference unless and until they address what I would call illegitimate power dynamics that are built into the status quo that we take for granted in business. For example, one is that the people with the money get to make the decisions. Why?

It's okay if the surgeon with the expertise makes the decision, but just because you're a private equity person who has tens of millions of dollars to offer me, why do you think your opinion should be the one that we follow?

Just because you're the tall, handsome, white guy should I quietly listen to you and not to her or not to him? The thing that feminism asks us always is to look at the power relationships and ask what are they? Are these fair and okay with us? If they're not, how do we change them? If they are okay, how do we articulate that and make it clear to ourselves and each other that we've accepted this and that it's fine?

If you are not always thinking about power dynamics, whatever kind of social enterprise you are, you're not going to make a real difference, because those power dynamics are at the root of all these business problems that our social enterprises are trying to resolve or trying to heal.

That's where the damage continues, that's where the damage comes from.

For entrepreneurs seeking to take action to dive deeper into feminist business, what books and resources would you recommend?

I was saying before that all these practices that we have in business, everything that we do in business becomes a site for innovation around power and flourishing. You can ask yourself, what are we doing? Is it our marketing, is our marketing possibly exploitative? Maybe I should go and look at Kelly Deals website and look at all the ways in which she's unpacking marketing and pricing so that we can see the power dynamics in the conventions and do something different. That would be one thing. Any of these practices, there are so many different things that are available out there for different elements of your business, but there are a couple that I think are profound and appropriate maybe to the Impact boom folks. The first one is this concept called Conscious Contracts. Conscious Contracting is a practice that started in the US in around 2010 by Kim Wright and Aliya Linda. They're two law professors and they wanted to put relationships at the centre of every legal agreement, and they wanted to find ways that we could make legal agreements be almost like the principles that we might establish at the start of a workshop; something that helps to develop and sustain a relationship rather than be all about what you can and can't do. They came up with this idea of Conscious Contracts, and I have a colleague who has a business out of Spain called Legally Unconventional, and she has taken Conscious Contracts and combined it with feminist business perspectives to ask, "how do we contract with each other in our business, in ways that are understandable, that value each other's strengths, that are mutual and that put the relationship at the heart?" Her name is Jacqueline Harani, and at Legally Unconventional, she has a website that explains what she does, and it's a great entry point into this concept.

Every single social enterprise has contracts, you have employment contracts, you have a sales agreement you have a lease on your building. You may rent equipment; you have agreements with your investors and all of those. If you rethink just a little bit about them, just a little, you make some move towards a situation that's less extractive and more mutually supportive. I know that there are a lot of folks in social enterprise who have begun to understand and really get excited about systems theory and systems thinking, and I always go back to Deborah Frieze and Marg Wheatley's books. They did that two loop model from the Berkana Institute about organisation and cultural change, and I love how they think about things, but again, what I'm always looking for is the one that's infused with feminist wisdom, the one that's infused with a sensitivity to power, and also one that asks, "whoever you are, wherever you are with whatever you bring, how do you make a difference?" There are two women who have this business called Systems Sanctuary. It's like systemssanctuary.com, and they're basically feminist systems practitioners. Rachel Sinha is one of them, and Tatiana Fraser is the other. They're both systems people who've started businesses and organisations that come together, and they do a lot of workshops that help you understand that wherever you are, you and a couple of your comrades can start to make change by understanding the system and they have a great way to understand system change through a different kind of leadership that's actually explicitly a feminist leadership approach. I love their work because a lot of people really get off on the complexity and the excitement of systems because we know it all must change, but then they think, "ugh, how am I going to deal with this?" You can't do everything, and if you have a good systems education and you know yourself, you can find the ways that you can fit into that system and start making a difference. I love their work. I know that you always ask folks to come with resources, and because I'm always being cranky about its practices, let the work drive the change as a theorist. I go out there and I say it's practice. There's this book that I love that came out just at the end of 2022, it's called Beloved Economies Transforming: How We Work, and it's by Jess Rimington and Joanna Sia. What they do is they argue that there are seven core practices of working together, and each one of those core practices is something we can mess around with, something we can play with, somewhere we can invite some liberation and some flourishing. They're thinking about how this is and an example for each of the seven practices, and I love it because it's practical.

The challenge of feminism and so many other worldviews is that the ideas are big and sometimes scary. You wonder, "how do I make this happen?" How do I bridge that gap? Anytime people can give us examples of that, I love that part.

I recommend Beloved Economies because it has a bunch of great examples, and the way that these women talk about what they're doing is accessible and it's beautiful. It's artful. They're very clear that they are writing this, but they are representing the wisdom of a large community. I always liked that. When I was writing my book, that wasn't something that the academic publisher I was writing the book for was psyched about! Then the other book that I wanted to recommend, or two others is I also harp a lot on this idea that this stuff has been done before, and I don't know why we don't go back to our history. Well, I do know why. It's because we've been told those histories don't exist or it never occurs to us to look for them. For a long time, the actual histories didn't exist, like I knew there were feminist businesses because I'd shopped at them, but it's not like there were books on it. But surprise, starting in around 2016, people started writing books on it, so I didn't have to read these obscure dissertations about bookstores in Salt Lake City, I could instead read a book like this one by Kristen Hogan, it's on the Feminist bookstore movement, which was in largely the late sixties, the seventies, and early eighties. It's particularly about that movement recognising the lesbian anti-racism and feminist accountability practices of the mostly women, but not always women who are part of this feminist bookstore movement. It hits a couple of things at once; feminist businesses have existed, here are how they worked, here are the chronic problems, here are the consistent joys and successes. You need to know this. But in the meantime, you probably don't know that much about Feminism, and you've probably been hearing about racism in the Feminist movement about how black women didn't count, how no one talked about racism how lesbians weren't part of it, they did their own thing etc. This puts context around that because these women were not all white. They were not all privileged, they were not all lesbians, and they worked it out over and over, sometimes effectively, sometimes not. They were grappling with racism in the Feminist movement with classism in the feminist movement, with other kinds of privilege in the feminist movement, and they were trying to figure out how to remain accountable to each other while they ran these businesses, which is the hard part.

As a business professor, I always talk about the revenue model, because if you can't make money, you can't do this organisational change stuff. But both of those things must happen at the same time. Then my husband reminded me that I should recommend my own book. Why? I recommend my own book about Feminism: A Key Idea for Business, and I have to say I did not pick the title (that was the academic publisher). The reason I do is because my book does three things while everybody needs as a foundation to talk about feminist business or for that matter, anti-oppression in business. First you get a primer on feminism; why it is the way it is, why I have that long definition, and so you come up with an understanding of what are feminist principles and practices and understandings? Not just we don't want this part, but we do want this other part. Then the middle section is looking at conventional ways that we understand business and comparing them with feminist ways that we understand business.

The conventional way of understanding a business, people hate it when I say this, but it's like they're basically systems designed to extract value and funnel it to the people who own capital.

That's what a business is. You can pretty it up all you want Whole Foods, but that's what it is. A feminist business can't be that, so how are they different? Then the last part is me trying to answer in serious ways a whole bunch of different questions that people have about if we had a feminist approach in business, how would we be addressing things like violence in the workplace or the role of bodies or occupational segregation, and stuff like that. That's trying to figure out how does it matter in all these chronic conversations; how does it change the conversation? I know that people don't walk into a business school bookstore anymore and pick up the thing with the bird cage on it and go, "oh, I think I'll learn about feminist interventions and business concepts.” But if they did and they thought about things like what it meant to centre a business around care, I think their minds would be blown. I think they'd go back in and say, "I love our focus on sustainability and environmentalism, how do we extend that to sustainably care for each other and sustainably care for our community? How do we expand our discussion of that?" When we're thinking about how do we bring products and services to underserved communities, how do we do that in a way that's not white saviour, in a way that's not paternalistic? How do we do that in a way that uses feminist design principles to go use their standpoint and our standpoint, to interpolate between them to come up with new insights. How do we do that? Getting an introduction to all those things, I think folks would get jazzed. Every now and then I'll get an email from somebody who's either done a Feminist Business Model Canvas class or one of my other workshops on like feminist accessibility and pricing or how to come up with a social justice accountability portfolio and accountability practice for your business. The number one thing people say to me is what you said at the start of this interview. Which is when I saw this, when I heard you say this, when I read this, I recognised it.

It resonated with me. It touched something in me, this wisdom that I knew was there. I knew I wasn't crazy. I knew that idea had value. People recognise their own desires for (it sounds so highfalutin but it's true) and they recognise their own experience in this.

They realise they didn't know there were words for this, they didn't know there were all these books they could read about it. They say, "I didn't know that I could think about my revenue model, not as something I'm going to pitch to investors, but as something that draws on my strengths and gifts." Anyway, I didn't even go on about the Feminist Business Model Canvas, but that's a great experience of just working through the whole Business Model [Canvas]. Even if you didn't know it was feminist, things would happen with you and your team as you went through it, because it's a stealth transformation situation. People hate the word, so many people hate the word feminism.

Petra and one of her colleagues were going to an Emirate, I won't say which one, but they were going to a Middle Eastern country to do a women's entrepreneurship bootcamp and they were hired by a bunch of guys in the government to help these women come up with their jewellery businesses or whatever they were going to do. Petra and her colleague wanted to use the Feminist Business Model Canvas, but they were afraid to use the word feminist because then the guys in charge of the program wouldn't let them do it. I made a different one, and we just called it the Values Led Business Model Canvas. Even if it doesn't have the word feminist in it, the experience of starting with your strengths and figuring out your insights and connecting with your customers and all that kind of stuff is crucial. It's a fundamentally different experience from working through something to make it really make sense so you can do your elevator pitch.

What were some of the key outcomes from working with those ladies when they used these frameworks in a different context?

Feeling like what they had to offer was real. They started feeling like they didn't have to pretend to be. Even going, backing up from that, having the experience in Petra and Val Fox's workshop of mattering, of having their insight and their desires matter and having that be the centrepiece from which they built out their business idea. It seems straightforward, but it's such a profound shift. It's one of those things that a lot of times I take for granted because now at my age I don't care whether I matter to you or not, I just talk. But also, I have enough privilege at this point, and that's why I have all this academic baloney in my introduction, because it establishes that I have the right to say things supposedly. But a lot of people, many of us don't feel that, and any time we can use a tool, that presumes you have a right and helps you start to unfold that. It’s about grounding you in a worthiness and an enoughness to build out from. When you're grounded there, it's so hard to run out. One of the things about a strength based or a personal wisdom-based approach is that stuffs always there. It never goes away.

CV, I’ve valued our conversation and there's just so much to learn. I'm very grateful for having you in today, thank you so much for joining.

Sarah, thank you so much for inviting me. I looked through many of the 402 people who've come before me, and I was just struck by the variety of people, but also by the repetition, in a really good way. The rhythm of all these overlapping viewpoints building. We have this concept I use a lot from Hilde Gottlieb called Collective Enoughness. We often feel like whatever we're doing isn't enough. If I'm only doing the Feminist Business Model Canvas, I can't teach you about collective decision making because I'm busy doing this. But when you recognise that we all do the thing that's our own genius or our own strength, but if we bring enough of us together in the collective, there's enough to do the work, and the beauty of looking at several of those 402 is you can see that there's enough overlapping that it's building to do the work, and every one of them you can listen to and you're like, "oh man, what a great thought, you're not alone." I think that's quite beautiful.

Initiatives, Resources and people mentioned on the podcast

Petra Fox, Val Fox

Recommended books

Feminism: A Key Idea for Business by CV Harquail

The Feminist Bookstore Movement: Lesbian Antiracism and Feminist Accountability by Kristen Hogan

Walk out, Walk On by Margaret Wheatley & Deborah Frieze

Beloved Economies Transforming: How We Work by Jess Rimington & Joanna L.Cea